The Sunk Cost Fallacy – Killing A Project That Should Have Died

Contents

The Sunk Cost Fallacy is used to describe throwing good resources after bad.

It’s when you’ve invested time and resources into doing something, and continue to invest in the project even when you know it is likely to fail.

As a manager, continuing to invest in a failing project means you’re wasting money and time.

More importantly, you will damage team morale as they will be able to see that the project isn’t going to work.

In addition, you can damage your own reputation. You need to know when to walk away from a project.

What Is The Sunk Cost Fallacy?

The sunk cost fallacy is a behavioural issue, as first described by D. Kahneman & A. Tversky, it’s perceived as a result of loss aversion in individuals.

They reached the conclusion that the sunk cost fallacy was real because people were more sensitive to a loss than a gain. After all, who likes to admit a loss?

As a manager, you’re probably afraid to admit you’ve failed.

Pumping more resources into a project keeps it alive, delaying the admission of failure.

Of course, ultimately the project will fail, and the more resources you’ve pumped into it, the harder it will be to admit your failings or to recover from them.

In simple terms, it’s like starting to watch a movie and realizing a short way in that you don’t like it.

Trainer Insight: On our line manager courses, managers admit they’ve kept projects alive as they were “already invested.”

Once they see that sunk costs can’t be recovered, they realise that redirecting resources sooner saves money.

Instead of turning it off or leaving the cinema, you continue, as you have already spent money and time watching it.

Sunk costs are gone and shouldn’t be considered when deciding future projects.

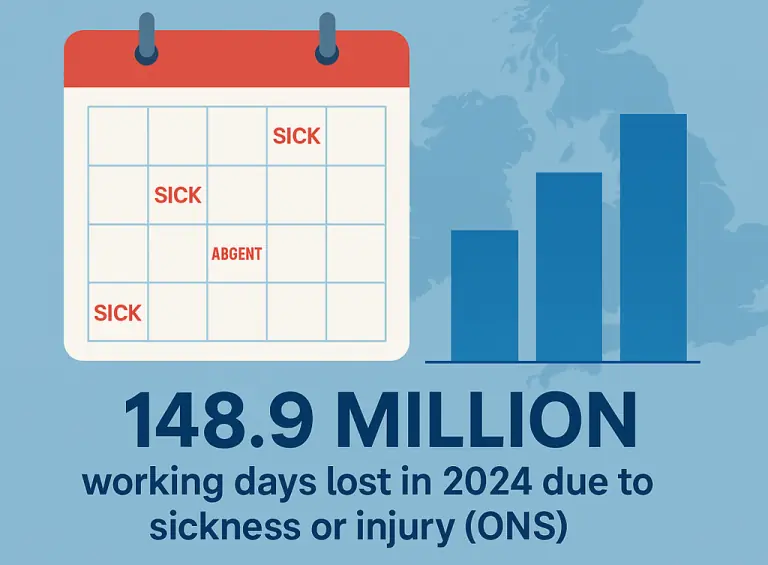

Allocating resources to a failing project deprives other projects of the capital they need.

The result can be fatal for a business, as product development falters and capital reserves are used up without the prospect of being replenished.

Why Leaders Fall Into The Trap

Managers are meant to lead, to appear like they know what they are doing. It’s hard to admit they have made a mistake.

This is especially true when dealing with projects, and any mistake will be clear to everyone involved.

In short, a manager’s ego can prevent them from seeing or admitting the truth about a project.

It’s even more likely this will happen if you were the manager who thought of the project idea.

Alongside this, managers are likely to fear the damage that will be done to their reputation.

The concern is that they will appear to be bad managers because their project failed.

However, the truth is, a project that isn’t viable will fail, regardless of who is controlling it.

A good manager will walk away, saving the business money and resources.

Management and employees will see that the manager was brave enough to step away and be more impressed with their abilities.

Of course, a manager struggling to make a good impression will struggle to see this.

Especially if they are being pressured to make the project succeed.

What better example of this is there than the VW scandal?

In this instance, VW committed to selling more cars in the US and shouted about how low the emissions were on their cars.

The project should have been halted when they realised the level of emissions they were after couldn’t be achieved. Instead, they invested more resources to create a sophisticated defeat device.

Sales increased, but today, company executives are in jail and the company’s reputation is in tatters.

Trainer Insight: We frequently see managers link their personal reputation too closely to a single project.

In reality, admitting failure early is often viewed by senior leaders and employees as a mark of maturity.

It shows you’re willing to put the organisation first rather than your own ego.

Changing Your Perspective

It is possible to avoid the sunk cost fallacy. You need to change the way you look at the project.

1. Embrace the failure as a learning opportunity

Every successful entrepreneur has a string of failures behind them. Just take a look at Sir Richard Branson, Jeff Bezos, or even Bill Gates.

Every failure moved them closer to success.

When a project is clearly going nowhere, terminate it. Make it a step to success by evaluating what was good and what was bad about it.

You can use that information to drive the next project.

Thomas Edison epitomises knowing when to walk away:

As he famously said, “I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.” Then he found the one that did.

2. Admitting failure builds respect

Continuing a failing project costs the business time, resources, and money. It damages staff morale and potentially the business reputation.

All of those things are bigger and more important to the company than your ego.

Once you realise this and stop the project, you’ll find everyone else was hoping you would do just that. The result is you’ll be seen as a better leader.

3. Remove Your Emotions

Take a moment to pause and look at the project objectively. Start with the resources used and results gained.

Then look at the future costs and potential benefits, if any.

It will likely be apparent that the project isn’t working.

Continuing with it is an emotional response; the inability to admit failure.

Stick to the facts and, if necessary, get a third party to evaluate the project.

When you remove your emotions from the equation, you’ll quickly make the right decision for the project and the business.

Trainer Insight: A useful exercise we recommend is to bring in a colleague outside the project to review progress.

External perspectives remove emotions and make it easier to spot when resources would be better spent elsewhere.

Leaders who build these checkpoints into projects find it far easier to avoid the sunk cost trap.

Practical Takeaways For Leaders

Everyone can make a mistake, even when you believe a project will be successful.

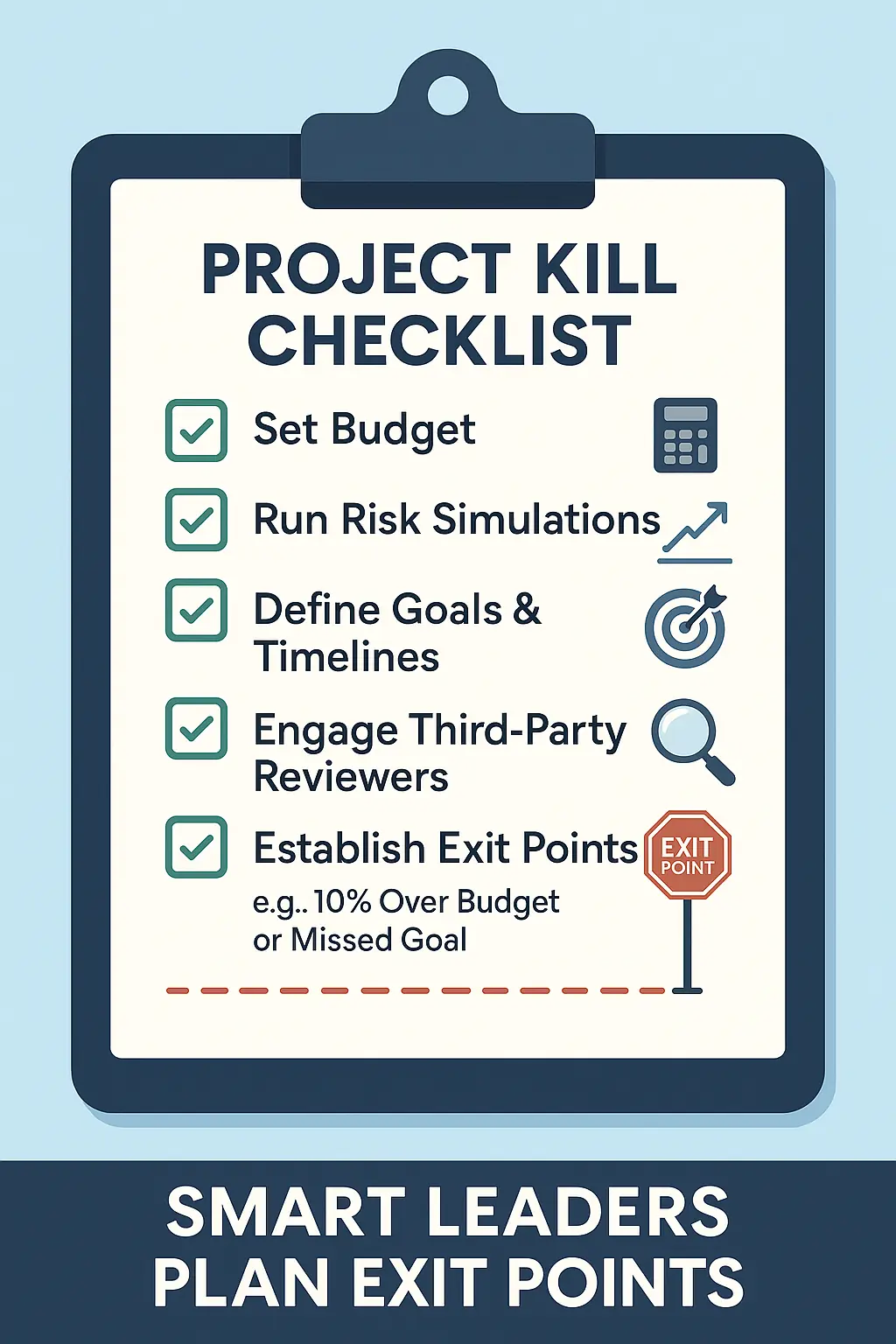

To avoid wasting resources and getting stuck in the sunk cost fallacy, create a framework for all projects.

- Start by setting a budget for the project and for each phase of the project

- Run a simulation of the project to understand where it is most likely to fail

- Set goals which need to be achieved by the project and timescales for those goals to be achieved

- Add a third party into the mix, separate from the day-to-day of the project, and get them to regularly analyse the project’s progress.

Alongside creating a framework, you need to decide points at which the project will be terminated.

For example, if it goes more than 10% over budget or doesn’t reach one of its goals. Setting these ‘exit points’ at the start of the project allows you to be objective.

It also creates a clear framework, making it easier to justify abandoning the project.

Another great tip is to listen to your employees!

If they are telling you a project isn’t worth it, it’s probably for a good reason.

You’ll find it easier to review a project’s progress against the original objective plan than you will to review it against your opinion of its progress after you’re emotionally invested.

Conclusion

Managers don’t need to be right all the time.

They need to be a strong leader, dedicated to what is best for the business and the employees.

In real terms, that means knowing when to admit failure and cut your losses. Staff will respect you for this.

Remember, every failure is a learning opportunity.

Evaluate a failed project with the team, you may be surprised at what you learn.

It can lead to ‘Eureka’ moments, like a phoenix rising from the ashes.

Don’t delay, run premortem exercises and decide on exit criteria before you start your next project.

It will help the project to run smoothly, and perhaps even be a success!

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100066814899655

- X (Twitter): https://twitter.com/AcuityTraining

- LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/company/acuity-training/